Susan Elliott & Paul Yip

The Canadian Index of Well-being was 11 years in the making and involved consultations with people across the country. The result is 64 indicators across eight domains: education, healthy populations, leisure and culture, time use, community vitality, living standards, environment and democratic engagement.

Hong Kong has one of the highest GDP per capita figures in this region, at US$56,719, but is not known for the happiness of its people; whereas Canada has a lower GDP per capita (US$44,310) but is seen to enjoy considerable well-being. The Bhutanese only earn US$8,077 but it seems the people are happy and contented. What really matters?

Since 1944, UN member states have used the gross domestic product as the standard measure of the economic well-being of their population. There has been debate about the use and usefulness of such a measure; does it really measure the well-being of people? To be fair, the primary architect of GDP – Simon Kuznets – understood its limitations. According to him: “Economic welfare cannot be adequately measured unless the personal distribution of income is known. And no income measurement undertakes to estimate the reverse side of income, that is, the intensity and unpleasantness of effort going into the earning of income. The welfare of a nation can, therefore, scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income.”

Measuring a country’s worth beyond GDP

Three decades later, Robert F. Kennedy went further, noting that the gross national product “does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials… It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile”.

So, what does make life worthwhile? We borrow a definition from Angus Deaton, the winner of the 2015 Nobel Prize for economics. Well-being, he says, refers to “all of the things that are good for a person, that make for a good life”. It includes “material well-being, such as income and wealth; physical and psychological well-being, represented by health and happiness; and education and the ability to participate in civil society through democracy and the rule of law”.

How is well-being to be measured? Understandably, such a measure will differ from place to place, allowing for the local context. For Hong Kong, Canada’s model of measurement may be instructive.

The Canadian Index of Well-being was 11 years in the making and involved consultations with people across the country, and a virtual army of researchers to develop domains for focus and indicators for measurement. The result is 64 indicators across eight domains: education, healthy populations, leisure and culture, time use, community vitality, living standards, environment and democratic engagement.

Deep blue: Hong Kong tumbles to 75th in world happiness rankings, lowest since UN report debuted

To illustrate, between 1994 and 2010, GDP in Canada increased by 28.9 per cent. At the same time, the Canadian Index of Well-being increased by only 5.6 per cent. In some areas it did well (such as education) and in others it did not do so well (physical environment). Thus, the index allows for composite comparison while also allowing for deconstruction down to its component parts for further analysis and policy response.

The advantage of this model is that it relies on secondary data – data already collected for other purposes – so it keeps costs low and timelines tight. This aspect of the model also ensures the sustainability of the index over time.

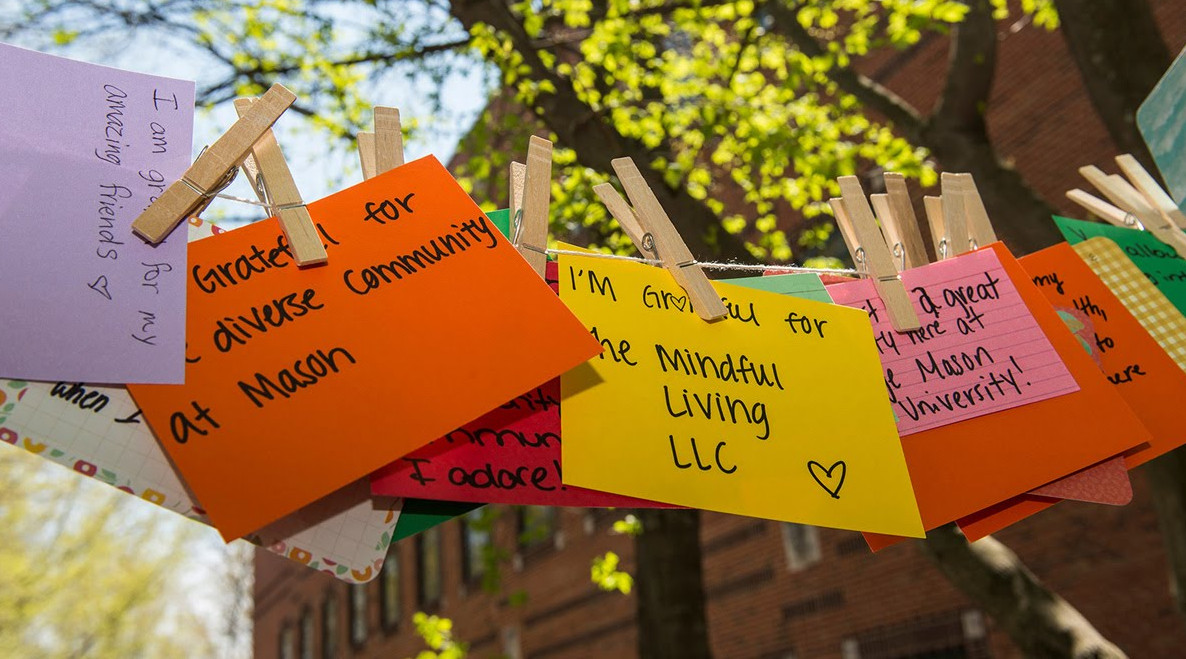

And while individual levels of happiness and satisfaction are important, a more useful measure of well-being is captured at the level of neighbourhood, community, region and/or nation. Research has consistently shown that for individuals to thrive, they need to be members of communities where others are thriving as well.

The Global Index of Well-being builds on this model, and preliminary research has been conducted on the transferability of the Canadian index to other contexts. Pilot work has been undertaken in Kenya, Ghana and Barbados. So far, consultations indicate it makes sense to continue using the eight domains of the index, even as adjustments must be made within each domain to allow for social and geographic differences. For example, while in Canada we measure the percentage of its population that has completed post-secondary education, in Kenya we focus on the percentage that has completed primary education and the percentage of girls who have had that privilege.

Li Ka-shing calls for higher profits tax rate to tackle Hong Kong wealth gap

Hong Kong has a high GDP per capita but also a large income disparity. How does a high average wage relate to our well-being? The top 20 per cent of income earners enjoy prosperity, the bottom 30 per cent simply give up hope and wait for the government to bail them out, and the middle 50 per cent complain about everything. It will be of great interest to see how Hong Kong measures up in the index.

In the end, what can one do with such an index? It can provide a solid baseline for the impact of economic growth at the national level and be a measure for evaluation in the face of policy implementation. The Hong Kong government is proposing to implement a family impact assessment in any policy formulation. Perhaps improvements in the well-being index can be used to measure the government’s performance. It is time for us to reposition ourselves in Hong Kong.

Many countries aspire to high GDP with low unemployment. We have achieved both. However, we have missed out well-being, and that is something we need to improve upon.

Susan Elliott is professor at the University of Waterloo, a member of the Canadian Index of Well-being project, and principal investigator of the Global Index of Well-being. Paul Yip is professor at the University of Hong Kong and principal investigator of the alleviating poverty project funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club

This article was published on SCMP on Tuesday, 19 July, 2016. Please click here to find out more.